Barbara Kruger – Subverting Subversion

Barbara Kruger is an American conceptual artist. Her work takes the visual language of mass commercial communication and flips it. Basically, she appropriates commercial photographic imagery and overlays it with philosophical slogans that run counter to the imagery. This inversion of meaning reveals how advertising reduces individual identity to that of a commodified object, forcing the viewer to recognize their objectification and react against it. These images are explicitly political, rallying against consumerism, particularly the objectification of consumers. More specifically, Kruger’s work rallies against the objectification of women.

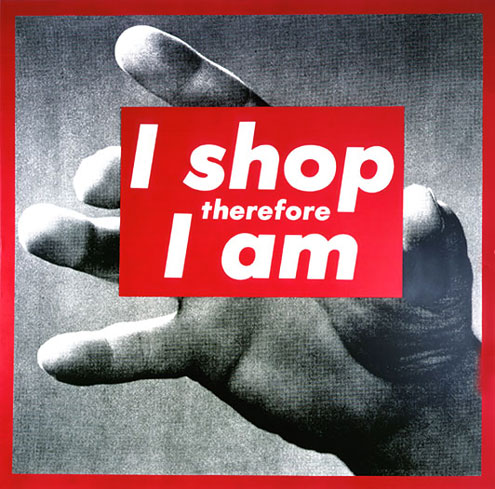

Barbara Kruger – Untitled (I shop therefore I am) – 1987

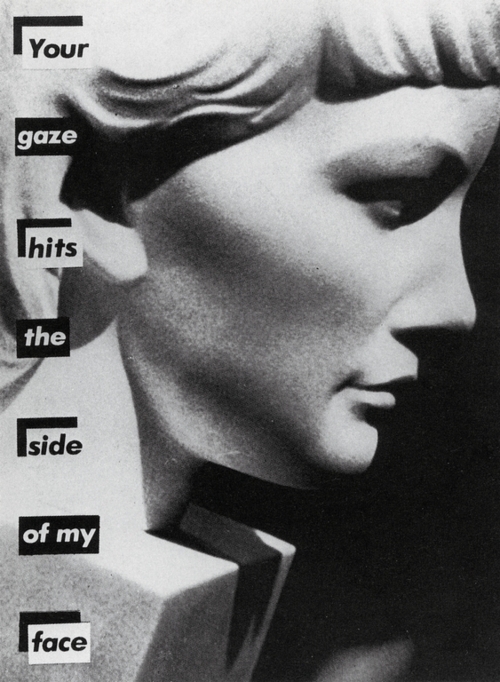

There are elements in Kruger’s work that not only critique consumerism, but also the objectifying gaze, and also patriarchal discourse. The idea behind the “objectifying gaze” is that the viewer is in a position of power that reduces the subject that is being viewed to the status of an object, as no back-and-forth exists in this relationship. For example, when a woman’s image is used in advertising, her identity is unimportant other than as a prop to the product. Patriarchal discourse refers to the wider social context. As we live in a male-dominated society, women are socially subordinated and are culturally suppressed in their means of communicating – like how there are so few women artists in the pre-1960s collections of art museums.

Patriarchy refers both to institutions and to discursive accounts of the world within which institutions are embedded. On the institutional level feminists have pointed to male dominance within family, state, religion, capitalism, education, and other social structures and have analyzed the practices by which male dominance is established and maintained. Further, feminist analyses of conventional relations between women and men show how male power insinuates itself into the psyches of women, teaching them to collaborate in defining themselves as subordinate to, and dependent on, men. Yet the experiences women have within patriarchy, especially those binding them to other women in recognition of their common plight, can be the source of feminist resistance.

“Patriarchy.” In Women’s Studies Encyclopedia, ed. Helen Tierney. Greenwood Press, 2002

Kruger addresses these issues to point out how within mass culture women are reduced to expressing themselves through their engagement with commercial culture, engendering a social context where social identity is only an emergent property of consumer behaviour.

Barbara Kruger – Untitled (Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face) – 1983

It gets even more complicated.

Kruger worked for 12 years as a designer and photo editor for Condé Nast, including magazines such as Mademoiselle, Home & Garden, and Aperture. Her use of the language of advertising is based on an insider’s perspective. The subversion of the juxtaposed slogans plays off of the viewer’s expectations where an advertising image supports the marketing call-to-action. This juxtaposition is not only a powerful subversion of a core marketing tactic, but effectively a snappy one-liner: the message is actually the opposite of what the image leads you to expect, get it?

This political humour would appear to be vital to understanding the deeper context of Kruger’s questioning of consumerism: her art is sold on mugs, t-shirts, postcards and posters in gift shops around the world. You, Barbara Kruger’s audience, like her work? Buy some stuff to show how you reject consumerism! Get it?

I have to admit, I decided to write about Barbara Kruger because I saw some rather frothy tweets raving about a pair of sunglasses. Limited edition, $200 sunglasses.

I was outraged and confused (metameat is me)

Yes, $200 limited edition anti-consumerism specs. Get ’em while they’re hot!

Limited edition sunglasses created in collaboration with artist Barbara Kruger and Freeway Eyewear. Kruger’s work is universally known for its bold, eye-catching design, and philosophical themes. Her iconic text Your gaze hits the side of my face appears across the arm of the L.A. RAYS style sunglasses by Freeway. This phrase first appeared in her 1981 artwork next to the profile of an anonymous classical bust. Presented on sunglasses, the wearer transforms into both a voyeur and an object; a play on themes of looking, power, and the gaze. The Kruger L.A. RAYS are available in three styles for pre-order now.

Give Good Art by For Your Art

Iconic? Did they mean ironic?

These sunglasses are a great encapsulation of the dichotomy that the larger Barbara Kruger product line represents. I’d honestly like to think that Barbara Kruger is aware of the contradiction of her commercial tie-ins and is doing it intentionally, but I honestly can’t find any evidence of that actually being the case. Take this snippet from an interview she gave in 1982:

Being socialized within similar constructs of myth and desire, it is not surprising that most people are comforted by popular depictions. Sometimes these images emerge as “semblances of beauty;” as confluences of desirous points. They seem to locate themselves in a kind of free zone, offering dispensations from the mundane particularities of everyday life; tickets to a sort of unrelenting terrain of gorgeousness and glamour expenditure. If you and I think that we are not susceptible to these images and stereotypes than we are sadly deluded. But to have some understanding of the machinations of power in culture and to still joyously entertain these emblems as kitschy divinities is even more ridiculous. And for women it’s an extreme form of masochism.

All Tomorrow’s Parties – Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince – BOMB 3/Spring 1982, ART (my bold)

I’d love to think that this is an elaborate Duchampian wit at play, but sadly, that does not seem to be the case. If, as Kruger asserts, self-aware women that buy into consumerism are masochists, what does that make Kruger for selling these sunglasses to her fans? A sadist?

[…] (greynotgrey.com) […]

[…] Share PostShare on FacebookShare on XShare by EmailCopy URL to clipboard Untitled work by Barbara Kruger (1987). Source […]