Back in September I mentioned Google Art Project…

I don’t know about you, but I often fantasize about winning a hefty lottery and spending the rest of my life travelling the world, visiting art museums. Google has come up with something kind of like that for those of us that haven’t won the lottery yet. With Google Art Project, you can search by artist name (in order of first name, oddly), artwork title, or museum collection. You can even sign up (for free) or sign in with your existing google account information, and create your own collections. Once you find a piece you want to look at, you can zoom in so close you can check the thread count on the canvas. It’s amazing.

Well, the team at Google has gone and improved it!

Here’s an update from +Google Art Project. Today we have 29 new art organizations from 14 countries bringing their collections online, and we’ve also introduced new tools—like a comparison feature and Hangouts within Art Project—to help you explore these great works even further. Read more on the post below, and of course, check it out yourself directly…

There is a ton of fantastic new content up, like work from the Princeton University Art Museum – here is an example of the level of detail you can get looking at, say, the Jockey by Toulouse-Lautrec.

- The Jockey (detail) – Henri de Tulouse-Lautrec

I know it sounds like something from Indiana Jones, but it’s true. Last month, the headlines looked like this –

Priceless Tibetan Buddha statue looted by Nazis was carved from meteorite

Relic taken by SS in 1930s analysed by researchers following reappearance at auction in 2007A priceless Buddha statue looted by Nazis in Tibet in the 1930s was carved from a meteorite which crashed to the Earth 15,000 years ago, according to new research.

The relic bears a Buddhist swastika on its belly – an ancient symbol of luck that was later co-opted by the Nazis in Germany.

Analysis has shown the statue is made from an incredibly rare form of nickel-rich iron present in falling stars.

The 1,000-year-old carving, which is 24cm high and weighs 10kg, depicts the god Vaisravana, the Buddhist King of the North, and is known as the Iron Man statue.

It was stolen before the second world war during a pillage of Tibet by Hitler’s SS, who were searching for the origins of the Aryan race.

It eventually made its way to a private collection and was hidden away until it was auctioned in 2007.

Nazi Buddhist Iron Man From Space

Crazy, right? Well, according to new studies, it’s not so much the case.

There were only, it turns out, a few slight catches. According to two experts who have since given their verdict on the mysterious Iron Man, it may have been a European counterfeit; it was probably made at some point in the 20th century; and it may well not have been looted by the Nazis. The bit about the meteorite, though, still stands.

– the Guardian UK

Nazi buddhist iron man from space, we hardly knew ye.

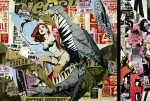

I’m a big fan of collage in its many forms. By its many forms, I mean traditional collage where people cut things out and past them back together using paper media or manipulating digital images, or even (as in this case) simply repurposing found art juxtapositions. This begs the question, “what is collage?” – I like Max Ernst’s definition best:

Collage is the noble conquest of the irrational, the coupling of two realities, irreconcilable in appearance, upon a plane which apparently does not suit them.

– Max Ernst

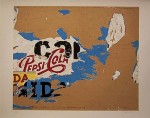

One of the things that I like best about collage is that once you’re used to it, you start to see juxtapositions in everyday life that, while accidental, imply collage in a found art sense. Sometimes the city makes its own collage – hence the title of this post. As posters and handbills are layered over each other, they get torn, revealing bits of the images and text beneath, creating a new image. A number of artists have seen this accidental collage and used it (or its semblance) to their own ends, like les Affichistes in the 1960s (Raymond Hains, Jacques Villeglé, Mimmo Rotella, and François Dufrêne) making art out of found torn posters on the street or FAILE today, who create their own artwork mimicking this effect and paste it up as street art (or more likely, now that they are recognised in the art world, sell them as limited edition prints, but you get the idea). Click on any of the images below to see them bigger.

- Dufrêne

- FAILE

- Hains

- Rotella

- Villeglé

Then, there is the “work” I see around the city – in this case, Montreal, where I live. Is it apophenia or is it an emergent property of urban life? Either way, these visual delights are something I always enjoy when I stumble across them, and when I see a really good one, I take a picture. Click any of the images below to see them bigger.

- Dufrêne

- FAILE

- Hains

- Rotella

- Villeglé

The biggest art market news from last week was the sale of a Gerhard Richter painting by Sotheby’s that has broken the record for the amount paid for the work of any living artist. I’m a big fan of Richter, so it pleases me that he has this kind of status in his lifetime, even if the £21 million paid for the piece goes to Eric Clapton – who bought it for a mere £2.1 million. The mind boggles.

Gallery technicians hanging Abstraktes Bild (809-4) by Gerhard Richter at Sotheby’s. Photograph: Linda Nylind

The picture, described as representing “calculated chaos”, sold for double its estimate last week to set a new record at auction for an art work by any living artist.

The previous record for a work by a living artist was set by the sale of Flag by Jasper Johns which sold for £19.5 million at Christie’s in New York in May 2010.

As might be expected form this sort of occurence, there is some backlash. One article goes so far as to ask whether the wrong Richter painting got the acclaim.

Gerhard Richter is possibly the greatest painter of our time, but the giant smear that is ‘Abstract Painting (809-4),’ which set a new ‘living-artist’ auction record at $34.2 million, could be mistaken for splashy décor …

… The issue with Richter may be that the photographic paintings that matter most in his career also can be rough to deal with. His greatest work is called Oct. 18, 1977, and consists of 15 blurred gray-and-black pictures of the Baader Meinhof gang, including paintings of several members after their deaths in jail. Over-the-sofa pictures these aren’t, but they’ve triggered reams of deep thought from some of the best minds around. It is possible, just, to go almost as deep with Richter’s abstractions, if you put in the work. But it’s also very easy to skim their surfaces.

I think Gopnik is a bit harsh, as I do see the point of Richter’s exploration of abstraction – after mastering representational realism, Richter experimented with a number of techniques that recall photography and question this kind of painting in the age of mechanical reproduction and photography. Richter would paint a representational realist piece and go at it with a squeegee. Going a step further and removing not only brushstroke but representational content is fairly obvious logical step. Richter’s paintings are just as much about the act of painting itself & the painter’s role within contemporary art as they are about any subject, and whether a piece like Abstraktes Bild (809-4) appeals to you or not is really a matter of personal taste. It is, however, an entirely valid point that Richter’s truly amazing earlier work like the Oct.18, 1977 series would never fetch these kinds of prices by collectors simply because the work is far more challenging – at least in terms of its figurative content.