I was checking through Drawger, and came across a great article by the extraordinary illustrator Yuko Shimizu on her illustration for a GQ article about the Japanese tsunami of 2011, selected for inclusion to the 2012 Communication Arts illustration annual. Anyhow, as I was saying, Shimizu wrote a fantastic article and I encourage you to read it: The Man Who Sailed His House.

It’s not every day a highly respected, award-winning illustrator explains how they work, it’s definitely worth the read. It’s really fascinating to see the visual process of looking through reference materials, building up rough sketches, moving on to black and white drawings, colouring choices, and the other kinds of choices that an illustrator makes when developing a piece.

For that matter, if you’re not already familiar with Yuko Shimizu, you absolutely must check her work out. She’s kind of a big deal (for good reason), having won tons of awards for her work with an impressive roster of clients. Well-deserved recognition aside, Shimizu’s work is all kinds of awesome, blending a range of tWe’ve all seen Asian/western fusion styles before, but Shimizu’s work definitely goes further than the hodegepodge of conventional style quoting we usually end up seeing. For example, here’s another piece of hers that I really like – an unused cover illustration for Time Magazine on the Tiger Mother phenomenon. It’s like Eloise in the land of traditional watercolours, mixing traditions from Asian and Western art to a very contemporary and unique effect.

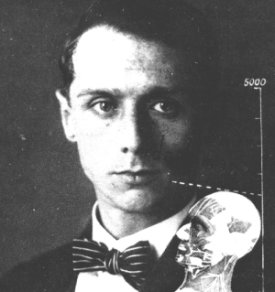

Before we get into Max Ernst’s surrealist masterpiece, Europe After the Rain II, we need some background. First things first: the artist.

Max Ernst (b. 1891 d. 1976) : founding member of Köln Dada; surrealist pioneer. That’s a pretty impressive byline, but with such a grand introduction it’s easy to overlook just how much Max Ernst contributed to art. For example, before Ernst showed up, collage was not taken seriously as an art form. This is the medium for which Ernst is best known – absurd juxtapositions of illustrations cut out of Victorian books often featuring grotesque hybrids of humans and birds, an ongoing theme in Ernst’s work throughout his life based on the childhood trauma of his beloved pet cockatoo dying the same night his sister was born. Many of Ernst’s collage series continue to be in publication, most notably Une Semaine De Bonte: A Surrealistic Novel in Collage, which is an excellent example of Ernst’s revolutionary work in this medium.

Collage is the noble conquest of the irrational, the coupling of two realities, irreconcilable in appearance, upon a plane which apparently does not suit them.

– Max Ernst

As a painter, Ernst invented the surrealist technique of frottage – making rubbings of textured surfaces and working with the forms that emerged. He developed upon this by inventing grattage – scraping paint off of a canvas with a textured surface underneath. He also developed upon the concept of decalcomania (an early image transfer technique) by pressing wet painted surfaces together, creating strange forms that he would then develop upon. These three techniques are related to the surrealist practice of automatism (free improvisation without self-censorship). Basically, these techniques are the artistic equivalent of rorschach blot tests – a means to channel the subconscious and allow the artist to escape the tyranny of meaning. Of course this also makes it hard to talk about what a painting “means”.

Max Ernst was born in Brühl, Germany and studied at Bonn University. He was already an exhibiting artist living in Paris when WWI broke out – as a German citizen, he was drafted by the German army and rather than face the prospect of being sent to a French detainment camp, Ernst accepted the draft call and fought at both the Eastern and Western fronts, mostly as a map charter.

Max Ernst was born in Brühl, Germany and studied at Bonn University. He was already an exhibiting artist living in Paris when WWI broke out – as a German citizen, he was drafted by the German army and rather than face the prospect of being sent to a French detainment camp, Ernst accepted the draft call and fought at both the Eastern and Western fronts, mostly as a map charter.

On the first of August 1914 M.E. died. He was resurrected on the eleventh of November 1918.

– Max Ernst

Over the following years Ernst built an impressive career as an artist. By the time WWII rolled around, Ernst was in France again, and this time was interred as an enemy alien in a detainment camp. His friends (including Paul Éluard) managed to get him released, but when the Nazis invaded France the Gestapo came looking for Ernst (who had been deemed a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis) and he escaped to the U.S. with the help of Peggy Guggenheim – to whom he was subsequently married. This brings us to 1940-1942, the years Ernst painted Europe After the Rain II while living in New York.

Europe after the Rain II – Oil on canvas, 1940-42. 54 x 146 cm (slightly smaller than 2×5″). Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, USA. (click for larger image)

This painting makes extensive use of the techniques Ernst invented, portraying a ravaged landscape reminiscent of both twisted wreckage and rotting organic proliferation. Are we witnesses to an apocalypse, or uncontrolled, cancerous growth?

True to Ernst’s methods, there is no definitive interpretation, but given his personal history, his flight from the Gestapo into self-imposed exile, and his disgust at the effects of war, it’s not hard to see a restrained melancholy on display.

In a landscape reminiscent of classical paintings of ruins, the figures could be overgrown statuary, or semi-mythical survivors of a forgotten war. A helmeted, bird-headed soldier threatens a female figure with a spear – or perhaps a ruined battle standard. Perhaps it is an allegory for the destruction of European civilization. Perhaps it is a denouncement, showing that once the dignified veneer of civilization is stripped away, only chaotic masses of half-formed nightmares remain. However you take it, Europe After the Rain II is a powerful image that provokes more questions than it answers, and a true masterpiece of Ernst’s ouevre.

For those interested in learning more about Ernst’s work, Max Ernst, 1891-1976: Beyond Painting (Taschen Basic Art) is an excellent book that includes many colour reproductions of the best of Ernst’s work including Europe After the Rain II and many others from this period of Ernst’s artistic career.

Ernst finally did move back to Paris, where he died in 1976.

I stumbled across some pieces by NYC artist Hope Gangloff and was really blown away by her approach to surface and pattern. She paints scenes from the hipster jungle littered with tats and empty PBR cans that evoke early modernist traditions of painting, with a totally fresh approach that goes well beyond the isms.

I looked around a bit more and found this article: Hope Gangloff: Memories in Acrylics – CHAOS Magazine.

I really enjoy this illustrator’s style, but the speed-painting video attached to this article is a great insight into the process of working with watercolour. Juxtapoz Magazine – Silvia Pelissero Watercolor.

I read today that Maurice Sendak has died.

I find myself overwhelmed with sadness. Beyond admiration for his incredible skill as a writer and illustrator, a lot of that sadness is nostalgia that’s tied in with the experience of Sendak’s books. So many books – and so different, so many styles. The most incredible thing about the diversity of approaches Sendak employed is that in each, for all their variation, it is still very clear who the illustrator was – every single one looks exactly like a Sendak drawing.

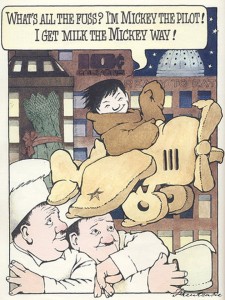

It is hard to imagine a childhood without the bold, vintage comic-book style of Mickey’s adventures from “In the Night Kitchen”. Milk! Milk! Milk for the morning cake!

Contrast this perfectly good illustration style with the playful cross-hatching in “Chicken Soup With Rice” (Sipping once! Sipping twice!), recalling Victorian era chapbooks.

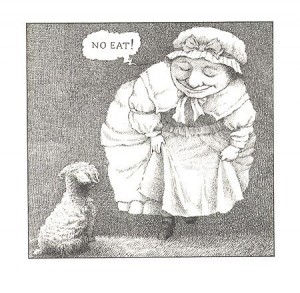

Moving right along, the intensely detailed inking of “Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life” is a marvel to behold.

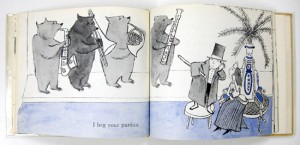

Another direction is shown in the whimsical, modern line and wash fills in “What Do You Say, Dear?” (An orchestra of bears!), representing another style that Sendak frequently worked with to excellent effect.

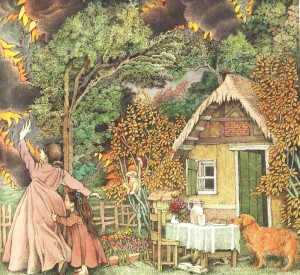

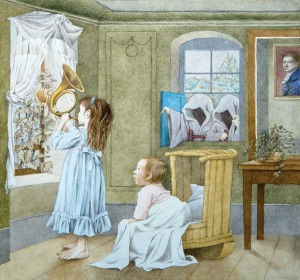

Finally, consider the stunning ink and watercolour lushness of newer, darker tales such as “Dear Mili”…

… or “Outside, Over There”.

Sendak was often criticized for the scariness in his tales, and was the frequent victim of censorship. Even so, “Where the Wild Things Are” is so universally popular because its intensity has so deeply affected generations of children and fired their imaginations.

Certainly we want to protect our children from new and painful experiences that are beyond their emotional comprehension and that intensify anxiety; and to a point we can prevent premature exposure to such experiences. That is obvious. But what is just as obvious — and what is too often overlooked — is the fact that from their earliest years children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions, fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday lives, they continually cope with frustrations as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming Wild Things.

Acceptance speech upon being awarded the Caldecott Medal for “Where the Wild Things Are” (1964)

How many illustrators could have built an entire career on just one of these styles, or one of these books?

Sendak illustrated over a hundred books and even his lesser-known work shows total mastery of his craft and a profound blend of seriousness and playfulness that verges on sublime. He won dozens of awards over his lifetime, basically every children’s illustration award worth having. It seems almost improbable that one man could be so talented, so prolific, and create such touching, lasting works.

Maurice Sendak was one of the greatest illustrators of the 20th century.

RIP, Mr. Sendak.